Reading about someone might be interesting, but it is nothing compared to meeting the real person. Alas, most of the prominent characters of Zen are long ashes and dust. For me, the closest experience to meeting face to face one of our Zen-ancestors is through their art-work, namely calligraphy.

Studying an old master-piece, the rhythm and energy of the brush strokes, the pace or slowness of writing is almost like seeing the person in action. Maybe more than a decade of practising and teaching Hitsuzendo, the Zen-Way with Brush and Ink, helps me to imagine a person’s character from the ink-trace he or she left on the paper.

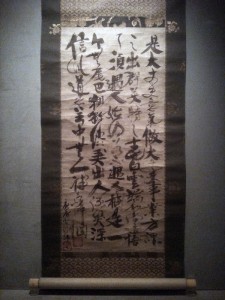

Wherever I travel, I visit museums or exhibitions having Chinese or Japanese calligraphy on display, and I feel grateful for having the chance to meet not just a few of my spiritual ancestors on my tours all over the world. Last week-end I met Ikyyu Sojun (一休宗純), the eccentric Zen-Master of the Muromachi period. Passed away more than 500 years ago, I like him because his life and action confronted certain aspects which are still an issue in contemporary Zen, namely selling Zen for money and condemning exchange with female. Ikkyu made quite a point concerning both aspects …

I met Ikkyu just “around the corner”, in the recently re-opened Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst in Cologne. Have a look at the picture I took, can you imagine what character Ikkyu was? A smooth, easy to deal with person? Someone who liked to make a point concerning what to do and what to leave? Someone vague, or someone decisive?

The piece was displayed in the framework of the exhibition „Mitleid und Meditation“: Der Mahayana Buddhismus („Großes Fahrzeug“) in Ostasien (“Pity and Meditation”: The Mahayana Buddhism (“Great Vehicle”) in East-Asia).

I wonder who made up that title? Why link Buddhism to pity (Mitleid), not compassion (Mitgefühl)? The question was not answered … and the longer I stayed the more I thought “what a pity!” The text by Ikkyu was not transcribed and not translated, the short text (and all the others) were only in German.

Quite speechless I was when reading the explanation concerning a statue of Ananda, one of the Buddha’s main disciples. It states, Ananda carafully listened to Buddha’s teachings and wrote down all his words. How could the curator of the exhibition ignore one of the most basic facts concerning the transmission of Buddhist teachings, that is, the strictly oral transmission for the first couple of centuries? Not just a little detail, as we all know …

No wonder in the second exhibition, a collection of old photography from the Museum’s late founder Adolf Fischer (1856-1914), Nanzenji was spelled “Nazenji” and a picture showing the Kaisando (開山堂) at Tofukuji in Kyoto was labelled as “Tofukuji, Nara”. We still know nothing about Asia, while Asia knows us so well. What a pity!