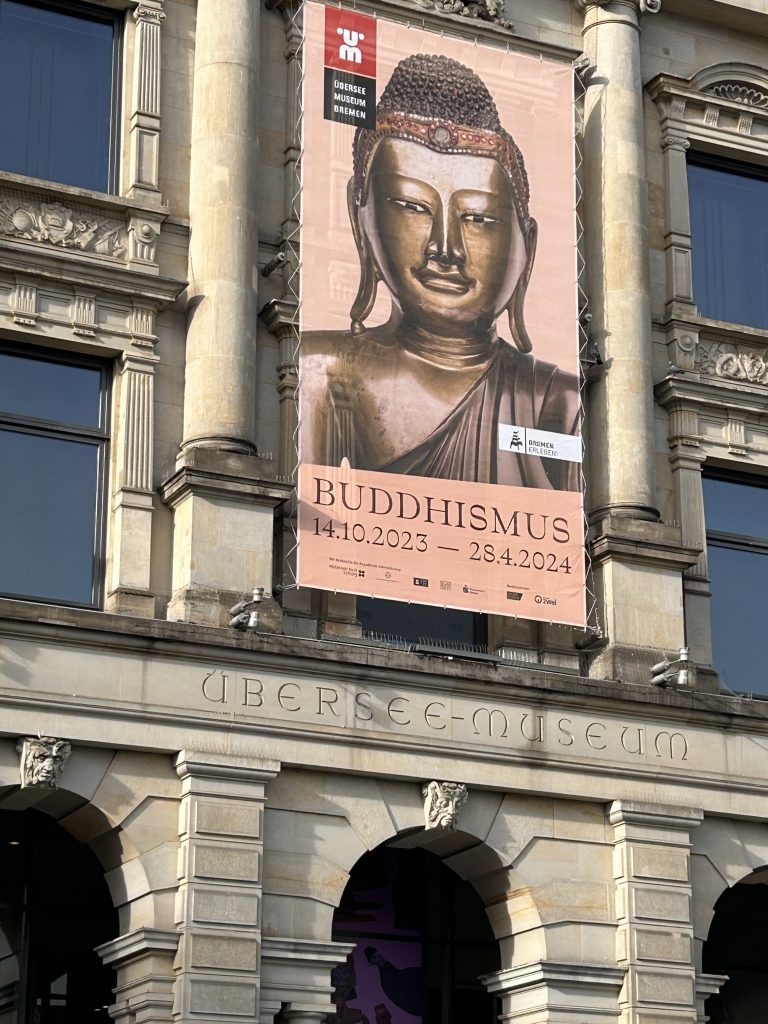

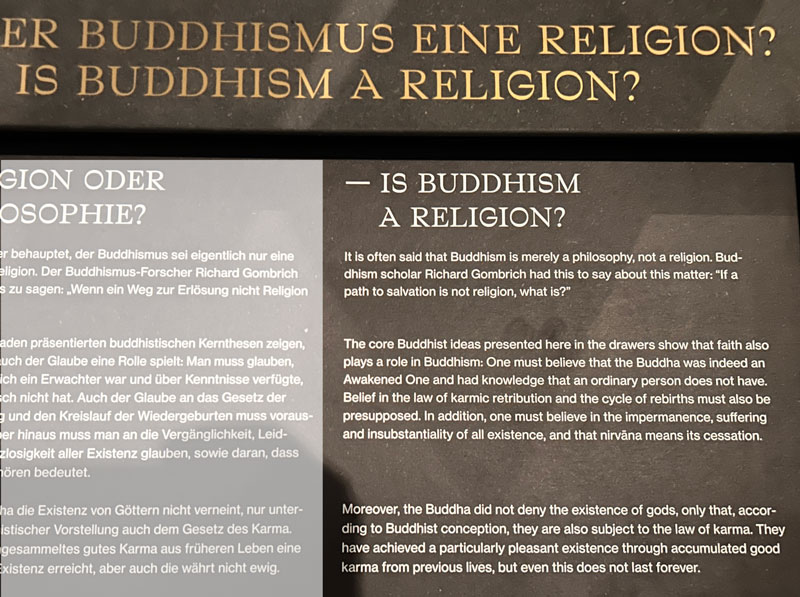

The other weekend we visited the Buddhism exhibition at Übersee-Museum Bremen. The focus of the exhibition was an attempt to proof that Buddhism is a religion to believe in, not something to understand. My oh my.

Was Buddhism meant to be a religion at all?

Did the person walking Indian soil more than 2.500 years ago had any intention that people over 80 generations later should worship his statue? Invent a whole pantheon of accompanying gods and spirits and mystify him as being the sheer representation of an ever lasting higher power (the existence of which, by the way, he vigorously denied)?

It starts all with a good human being, an intelligent and compassionate man or women. And it ends up with well-fed elderly men (and very few women) in expensive brocade robes who succeed to impress their followers by fairy-tales of their imagined spiritual faculty or exclusive relation to godly creatures. It is called religion.

The Zen tradition as a branch of Buddhism makes no difference, and no doubt, this is a very big misconception. A fatal misunderstanding of the initial intention, with the only positive side-effect that powerful and wealthy institutions ensured to forward the message over centuries and millennia, however distorted it may appear nowadays.

Our digital generation these days enjoys the privilege of an almost unlimited access to information. We are the first generation ever who is able to easily access whatever we want to know about anything without being dependent on the goodwill of a specific person or institution. At least, in the free parts of the world.

We have all we need at our hands to dust and clean what came down to us through centuries of Buddhist tradition. Like no generation before, we can try to reconstruct what this one person we call “Buddha” did and said, as good as possible understand his intention, no matter how this or that tradition claims to convey the true story.

We have all the material at our hands. With a bit of effort we can research by ourselves how ancient texts developed into the very Sutra we maybe chant today in our local Sangha or Dojo. We can follow the development or distortion of certain ideas through the centuries. We can see how Indian Hinduism re-infiltrated Buddhist ideas. We can study how local folk religion merged with specific lines of Buddhism, for the good or the worst.

The person who spoke of himself as the Tathagata was not a Japanese Zen Master. And he did not issue any certificates to his students (just a flower, instead of). He also had no Buddha statue to worship, though he had a particular sense of humor, often making fun of the prevalent religious believes of his time and region. As far as we can know, he did not worship any gods.

Spiritual era’s gone, it ain’t comin’ back.

Bad Religion, a copout, that is all that’s left…

Don’t you know blind faith through lies won’t conquer it

Bad Religion

Don’t you know responsibility is ours?

I don’t care a think about eternal fires.

Said that, possibly we should not give up all tradition and rituals. It may be helpful to have a substantial and supporting practice and a strong connection to every day life, since intellectual understanding is limited to just this: intellectual understanding. It can only serve as a map, as a cooking recipe. The action of going, cooking and eating is what counts, not of studying map after map or memorizing recipe after recipe.

Let us not be intimidated on our way by titles and brocade robes, by the dust and rubble the traditions accumulated over centuries. We may well find a treasure covered by all that scrub and layers of dirt. At least as long as we take the effort to dig deep enough and don’t forget how to use our brains instead of being satisfied with just believing in a bad religion.