Out of Sync

I imagine our Dojo, as it is, would be shifted 300 years back by a magic time machine (large enough to fit our Dojo in). How would that affect our practice?

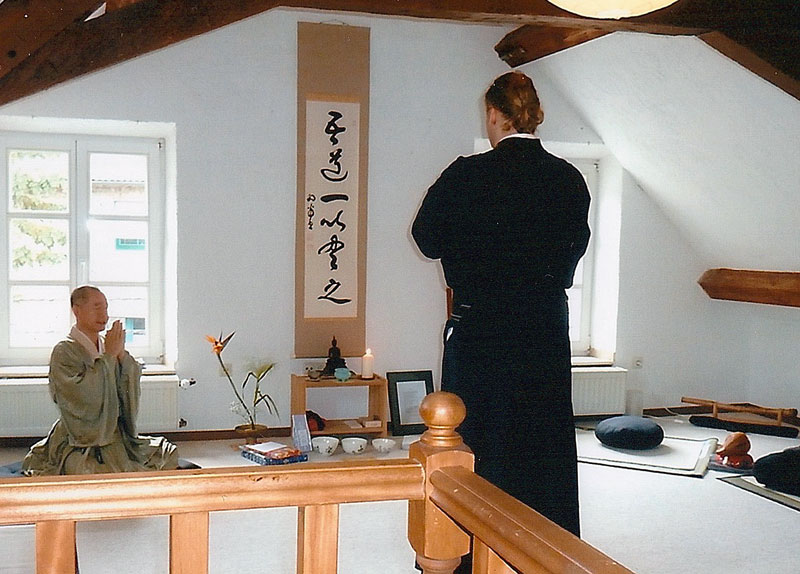

For evening Zazen and Hitsuzendo we had to use candles or oil lamps. Fetching water would require us to walk three minutes down to the nearby river. That’s basically it. Nothing else would change … our exercise is timeless. Kind of.

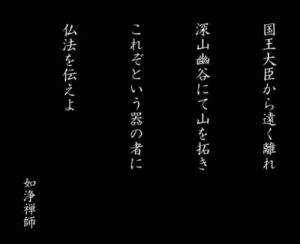

On the other hand side, most of the eight cushions in our Zendo remain empty most of the time. In spite of an attractive program, very few prospective new students come through the door, even fewer come back a second or third time. What we have to offer in this digital age of TicToc/Instagram/Selfie madness, the ancient practice of Zen Meditation and Calligraphy with brush and ink in the style of a more than 1500 years ago passed away Chinese master, seems totally out of time.

Du hast dich selbst überlebt, die Edlen überlebt.

Goethe, Götz von Berlichingen.

We love our practice. Every time we meet and sit together and write together with brush and ink, every time we practice Aikiken with our wooden swords we agree this is a “perfect day”. It has become our “Way of Life” over the years, and I feel most grateful towards my young student who joined me a couple of years ago, and stayed.

A long planned Sesshin in Bavaria this November was recently cancelled last minute, only three people registered. I wonder. What a chance missed!

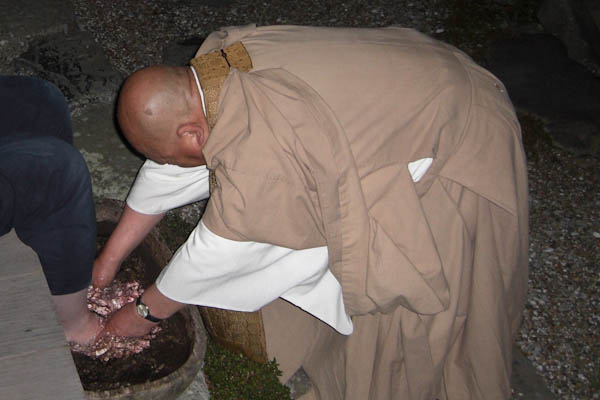

It took me ten years to find my teacher (before the times of internet, how to search?), and ten more years studying with him, before we were teaching together. Then, side by side, for three more years, we were leading our Sesshin together. It was my younger years achievement finding a suitable teacher and learning from him. After ten more years working on my own I slowly reached sufficient confidence to share my way of practice with others.

Am I hopelessly out of sync, unable to catch up with all the benefits of our the digital 21st century? I don’t think so. In my bread and butter job I use all modern technology available, Computers, Simulation Software, AI, … my office is 100% paperless and all communication occurs digitally via my laptop. I could do my job from any place on earth with a sufficient internet connection, matching the state-of-the-art definition of a modern digital nomad.

Privately, I write letters to my friends, by hand. I enjoy conversations lasting several hours without looking once at my mobile. I remember what we talked, I think about it and I might get back to it, revising my yesterday’s opinion. I prefer listening to music real human beings perform, life on stage. And if not available, I substitute by listening to a record, or CD.

I am old enough to remember “You want to see my record collection?” as a suitable pick-up phrase. In Murakami’s novel ノルウェイの森 (Norwegian Wood) the main character has a part-time job at a record store, and listening to a record he brought to his maybe love Naoko plays an important role in the novel (and for the title, obviously). Hard to imagine in times of streaming and endless playlists such thing could happen.

When I was in my student years, learning something required to find someone who knows. And to make him or her spend time with you, until by and by you yourself became somebody who knows. Learning involved conversation and interaction. And even if one preferred to learn mostly by reading, having someone to recommend the next good book was indispensable (that was the most important task of a good book shop, before Amazon entered the scene). Exchange between human beings was essential.

Now we have the internet, google, Wikipedia and AI. Soon, everyone can live in his or her own personalised AI bubble: virtual friends, partners, AI generated music and movies. Everything out of the box, available 24/7 and suited according to your very preferences: the ultimate climax of loneliness.

We instead keep doing “the real thing”. At our unheated Dojo, sitting on a cushion with our own body, writing with brush and ink on real paper on the floor. Exchanging ideas we are not sure about. Trying out this or that, and most important: having a good time together. Real humans, with all their flaws and shortcomings involved in a dedicated practice of ancient Japanese arts. This is so beautiful!

If lights go off tomorrow, if the Internet and AI shuts down, we will continue. Not much change required …