I have never in my life heard anyone playing the shakuhachi like this. A tune the master produced on his bamboo flute came from far away and long ago. He never said a word too much, and the tea-time before our lessons often was a silent, speech-less distress during which I desperately tried to find the one or other topic for conversation.

“So, bitte spielen Sie!” (so, please play) and “Ja, noch einmal!” (yes, once more) were probably the two phrases I heard most from him. Some lessons passed without much more than “So, bitte spielen Sie!” followed by two or three “Ja, noch einmal!”. He played a tune, I copied to the best of my limited abilities.

For ten years month after month I visited him, either for a private lesson at his home in northern Germany or during his regular class near the Bavarian Alps, each a day-trip away from my home. Learning the shakuhachi required lots of commuting to these locations, one with its low sky, rough winds and the nearby salty sea in the air, one with the sight of majestic snow covered mountains. Playing a tune from his hand-written music scores on the flute he once made for me always evokes images in my mind of the surrounding nature where I once studied with him. And though it should imitate the sound of a bell ringing in the empty sky, I can hear the sea and the wind in the snowy mountains as well.

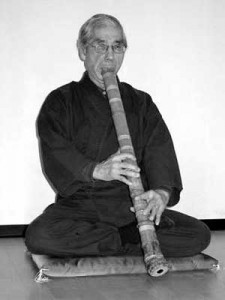

The way my former teacher expressed himself was mainly through his shakuhachi, which in ancient Japan was exclusively played by the Komuso Monks while begging for alms, and sometimes used as a weapon to defend themselves. For him, it never became a musical instrument amongst others, the way we nowadays usually listen to the shakuhachi. His Kyotaku is a tool for meditation, for practising Suizen (吹禅), or “blwoing Zen”.

Ikkei Handa passed away on 1. October 2014.