I drafted this text some years ago, when I had many more students at my Dojo and did most of the chores alone. For some reason I never published it. Now we are just a few and perform all tasks together.

–

What is your role within your group, your Sangha, your Dojo?

When you are new, arrive at the doorstep of a Dojo for the first time in your life, it is pretty clear. You are 初心者 “Shoshinsha”, a person with a fresh beginner’s mind. A 初心者 is nothing bad at all, not as the common English translation “beginner” might imply.

In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.

Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

Don’t worry what the seniors or teacher at the Dojo might think of you. Never consider impressing them with some previously acquired wisdom from books or the internet. Just be polite and watch carefully, try your best to join in and all will be fine for the 初心者.

With time, to my experience, the beginners develop into two directions. Many of them are becoming the equivalent of a permanent guest. They arrive last minute, enjoy a clean Dojo and a prepared setting for their practice. They make use of every occasion for some small talk and enjoy “guiding” new members of the group. Usually they are very nice and friendly people and there is nothing wrong with them, except that I don’t really understand why they prefer to spend their leisure time at a Zen Dojo.

Some, few, soon realise it is not my task but their task to run the Dojo. To keep it clean, to bring flowers, to prepare everything for their practice. This realisation sooner or later results in the question

Can I help you?

My true and honest answer to this question is usually “No, not yet!”. Why do I say so? Why do I not explain what to do, and give the motivated 初心者 a task?

The reason is twofold: I simply have no time to name and explain the many many chores which are to perform in a Dojo. Instead, I demonstrate it myself, with my whole body and mind, every day. All you have to do to find out how you can help is: carefully watch me doing how and what I do, in which way and what order. And then do it, before I have to do it.

All I do at the Dojo I only do because there is no one who completed the task before me.

This is how I learned. I watched my teacher, and whatever I realised he is doing, next time I tried to complete before he had a chance to perform the task by himself. Of course he often had to correct me, not by words, but just by redoing what I did in a wrong way. For me, that meant watching again and doing better next time. Occasionally he also had to stop me from doing something. Understanding when to do what from morning to night, especially during a Sesshin, is not a simple task which can be learned within one or two years.

Looking back at those student years, I feel a bit embarrassed, because I thought as an assistant I helped my teacher doing his work. In reality, as I realise now, he was taking the burden upon his shoulders to teach me. Instead of quickly performing all the tasks by himself, he had to carefully observe me trying my best efforts. Always ready to jump in or correct my wrongdoings early enough before the flow of a Sesshin or seminar was interrupted. I was a bit like a student at a driving school, imagining to help his driving teacher driving the car.

After ten years or so I was more or less running our Sesshin alone, my teacher was just present in the background. I admired his ability to withdraw, to let me take his seat (literally, we changed seats in the Zendo). “I arrive 14:30 by train, only bring tooth brush and pyjama!” was his usual announcement before Sesshin during our last two or three years we spent teaching together. The rest was upon me.

When I opened my Dojo and began running Sesshin completely on my own, that was just a small and natural next step. Nothing special. Although my teacher was not my teacher any more, and he was no longer present in the same room, his presence was imagined by me all the time. It was me, but yet at the same time still him running the seminar. I even imagined hearing his voice every now and then, warning me before I did the one or other mistake.

Consequently, the first ten years working without my former teacher were mostly learning to become free of his pervasive presence in all my doing. I never imagined this would be the most demanding and difficult exercise he left for me! And even today, there is hardly one class, one Sesshin where I do not mention or quote him.

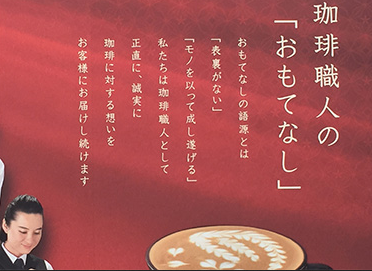

How do I look these days upon those “guests” who arrive three minutes before we are supposed to be on our cushions? I do so with 表裏なし (omoteuranashi). It sounds a bit similar to the well known お持て成し (omotenashi), which is often translated as “hospitality”, yet the 表裏なし literally means “no front and back”. By showing openly everything from all sides I perform at the Dojo and during a Sesshin, I have no hidden back, no secret ways and hidden routines.

It is never too late, even for a long term guest, to begin watching carefully …

–

(1) Picture taken from https://tak-shonai.cocolog-nifty.com/crack/2016/04/post-643a.html (accessed on 5. August 2023). The coffee advertisement gets the etymological root of おもてなし (omotenashi) wrong by naming its source as 表裏なし, as the Japanese blog post points out.