“You are like a shark” she said, her beautiful eyes filling with tears, “you can’t stop moving, or you’ll suffocate and die!”, half scared that I’m almost gone, half aware she can’t stop me anyway.「馬鹿いってんなよ!」was my pretty rude reply, purposely ignoring she understood too well what was going on.

Looking back, amongst the best I used to do was moving on before things turned bad, the worst staying for too long. Not just in the most troublesome and most joyful adventure of romantic encounters and exploring the heavens of mutual physical attraction.

I left my home-town, my childhood and teenage friends. I changed my subject of research, my field of expertise end eventually even my profession. I left teachers behind and cut off with anyone who was stealing my time or energy. I gave up believes and convictions, ways of looking at people and the world, stopped doing things I “always” used to do. Not because I wanted to, often not even because I decided to do so for the one or other good reason. Staying with what felt wrong gave me such physical and emotional discomfort that I almost couldn’t breathe. I had to move on … like a shark, who never stops moving. My wise friend with the beautiful eyes was probably right.

In Buddhism we often talk of “impermanence” (anicca in Pali, 無常, MUJO in Japanese). Intellectually understanding impermanence is no big deal: absolutely everything is always changing. Fully accepting this as the underlying structure of our whole life is yet a different challenge. Just for the ease of understanding, let’s stick with the Mating Game: “Stay as sweet as you are” (Nat “King” Cole), “Stay with me” (Sam Smith), “Don’t change on me” (Alan Jackson) sounds the plea of (mostly male) love-songs, not to anyone’s surprise followed by “Why did she have to leave me?” (The Temptations) and “Baby, please come back” (Eminem & 2Pac).

While scuttling around in the shallows of couple counseling, some more mainstream pop wisdom on accepting impermanence, “Let it be!” (The Beatles) and the Nobel Price awarded “Don’t think twice it’s all right” (Bob Dylan), is probably the better advice for soon to be (or far too often) broken hearts:

You’re the reason I’m a-traveling on (…)

Where I’m bound, I can’t tell

Goodbye’s too good a word (…)You just kinda wasted my precious time

“Don’t Think Twice it’s All Right” (Bob Dylan)

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

When being in contact with the world, when enjoying sensual pleasures, craving for and eventually clinging to what is constantly changing can cause tremendous pain. The whole chain was explained many times and in various detail by the Buddha as Pratītyasamutpāda (dependent arising).

Sometimes, though, I doubt. I turn around to see again past friends, teachers or even a love I left behind for good, and almost always I deeply regret coming back. The most painful insight Buddhism and Thermodynamics have in common is that the Arrow of Time cannot be reversed. What we call 無常 (MUJO) within Japanese Zen is almost equivalent to the Second Law of Thermodynamics in modern Physics. Entropy tends to increase over time, with the most surprising and beautiful but ephemeral local exception we call “life”.

How should we live our life, embracing 無常? Where to cut the chain leading to suffering?

I tend to disagree with my old friend A who became a Bhikkhu (monk) in the Theravada tradition many years ago. He decided to strictly follow his adopted believes and avoids contact with everything (and everyone) that might provide him with feeling and sensual pleasure.

Different from his approach, I prefer to endure the craving as an integral part of human life in the face of impermanence, of fully being in contact with the world. Leonhard Cohen is probably right, there “Ain’t no cure for love”. Yet, by any means, it is crucial to avoid clinging to what one cannot get hold of anyway. “Always Let Me Go“ (Keith Jarret) is not just closer to my taste of music than any love song, it conveys a deep understanding of how to to deal with impermanence.

How to live a life, when everything is on the move and beyond our control anyway? Shouldn’t we just give up and let it flow? Why to engage with a certain practice or Way (道, DO)?

「転石苔を生ぜず」(てんせきこけをしょうぜず), a rolling stone gathers no moss) is a well known Japanese proverb, emphasizing you should stick with whatever you do for a long time to mature. Just jumping around makes you a jack of all trades, a beginner in thousand arts and subjects.

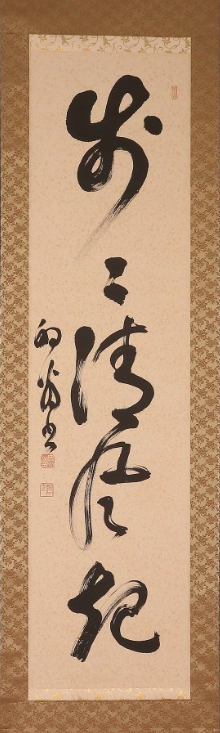

「歩々清風起」 (ほほせいふうおこる) is yet another Japanese proverb from the Zen tradition. It translates “Step after step, fresh wind arises”. A cool fresh breeze comes by itself, as long as you move on. For our Dojo’s art collection I recently acquired a beautiful scroll 「歩々清風起」written by my former teacher’s late teacher Oomori Sogen (大森曹玄).

This calligraphy brings me to full circle of “should I leave or should I stay ?” Was I meant to becoming the stone collecting moss, or made for enjoying a fresh breeze while moving on? Is this even a contradiction, an either-or question?

I left my former Zen- and Calligraphy teacher more than a decade ago, after thirteen years of being his dedicated student, but I still practice in the tradition of his lineage, of the past masters Tesshu Yamaoka and Oomori Sogen. I will do so as long as I can hold a brush.

I left my first Aikido teacher after only 3 years, while I was still a University student, and the following decades I engaged with lots of different styles, martial arts and teachers. But I still practice Aikido in the style I first encountered, the Aikido of the late Kobayashi Hirokazu. I hope to one day exhaust my last breath while flying across the tatami.

I left many friends and lovers behind (and many more left me behind), but I never get tired exploring the fascinating miracle of being with someone who is not boring, who does not waste my time. We might even fall in love, without intention … but promise you will leave, not die!

Juliet: Wilt thou be gone? It is not near day;

It was the nightingale, and not the lark (…)Romeo: It was the lark, the herald of the morn,

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act III Scene V

No nightingale. (…)

I must be gone and live, or stay and die.