One example of duḥkha listed by the Buddha is “association with the unbeloved”. If I was more educated in English literature and had known “Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes” by Robert Louis Stevenson, I would possibly not have agreed to the holiday I just returned from. Also the slightly cheesy movie Antoinette dans les Cévennes could have warned me, if I had not heard about it just three days before I put a saddle on a donkey for the first time.

By six, we began to load the donkey; and ten minutes after, my hopes were in the dust.

“Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes” by Robert Louis Stevenson

There is generally nothing wrong with donkeys or hiking with a donkey. Donkeys were domesticated long before horses, and have been used as means of transport for at least 6000 years. Yet there is something specific with the psyche of a donkey which is hard to decipher for us humans. After the trip, the donkey master told me “we try to understand the donkeys’ psychology our whole life long, but we fail”. Possibly this is because donkeys shared 6000 years of co-evelution with us, perfectly enabling them to read our minds and identify our week points without fail, while disguising their own intentions in amazing variations of play-acting.

I experienced “our” donkey as blessed with the soul of a highly intelligent, yet incredibly lazy and unbelievably hoggish stubborn five years old kid. Imagine you try to motivate such kid to get up from the sofa, stop eating and carry your luggage through the French Alps for seven days. A kid of 400 kg weight, enormous strength and a rather short-term memory concerning any action-consequence logic.

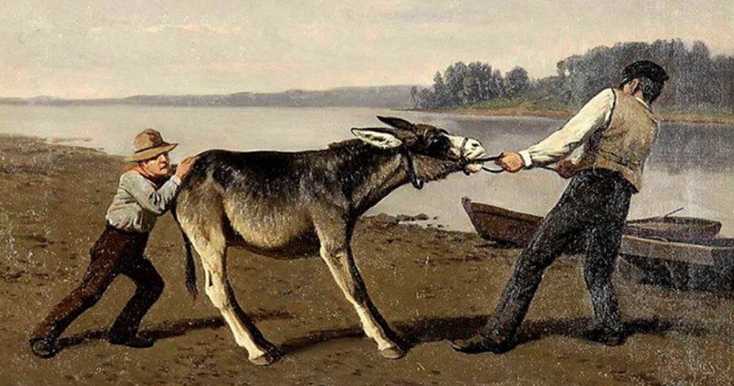

Opposite to a stubborn kid, it is impossible with our limited human force to move a donkey who is determined to stand, or stop a donkey who is determined to move. And the donkey is very well aware of this fact. The only thing that worked out was me walking behind the donkey whilst applying exactly the style of “communication” with the animal the donkey master had previously (to the horror and dismay of our little daughter) demonstrated to me. Sparing details, a strong kiai and the ability to efficiently use my body weight from decades of Aikido training came in quite handy. The donkey appeared to remember my determination to keep him going for a certain time-span, from a few minutes up to half an hour. Then I had to convince him again that the journey goes on, together with him. In case I walked in front just holding the rope, our donkey made unmistakably clear I have no chance to pull him. If he wished so, we could walk. Usually he preferred to stand still and watch me pulling, or started eating. As soon as he sensed I am going to walk towards his back, he began to move.

It is now impossible to push from behind and at the same time lead from the front. If I have to be behind and pushing with fierce determination, I cannot walk ahead, scout the way and lead up- and downhill the often steep and narrow mountain paths. I cannot spot suitable places to rest, make sure the path is safe and wide enough for the loaded donkey to pass, or that we are still on the way we planned to go.

One who is busy pushing and making sure things are moving cannot simultaneously scout and lead. And who walks ahead finding the path must rely on the rest of the crew following without the necessity of wasting time and energy with pushing from behind. As I mentioned before, in Zen training I prefer not to act as a pusher. Actually, I hate pushing, donkeys as well as students. What I prefer is scouting a way and trying to walk it first, find a safe path and good places to rest. What I am not interested in is pushing from behind to make sure everyone is coming my way. I guess, this attitude totally disqualifies me as a donkey master.

Said all that, I sense a certain momentum to contradict my kitchen psychology concerning donkeys and ways to make them go by alternatively employing loving kindness. Occasionally when the path ahead promised to become a bit unpleasant while the fresh green on the roadside looked even more oh so tasty, I had to become louder than usual to demonstrate our friend my unshakable determination we are going to move NOW.

This was the very moment when the donkey huggers came. With a fierce look towards me she approached the donkey and began softly talking to him while affectionately petting his head or putting the arm around his neck. Yes, she was sure that the lazy five years old big eater can be convinced by sweet words to stop snacking and instead start progressing with his heavy chore. Not. Fortunately not, since in case the half ton load starts moving, the bags extending on both sides will inevitably end the sweet rendez-vous by pushing the donkey whisperer down the hill (I experienced that painful encounter with the load more than once). So instead of just shouting to the donkey, I also had to shout towards the fearless lover of beast “stay away, it is dangerous!”. If you have to push, inevitably you will be interfered (and hated) by those who decided it is their holy duty to stand by those who need to be pushed. And you have to push them as well, to prevent further harm. Needless to say, the donkey exploited such welcome event to engage once more into eating.

Maybe I was a total failure with the donkey you might think now. Maybe I was too fierce, or not strict enough. From time to time I thought so as well. A few episodes convinced me otherwise. Once going downhill with the donkey at quite a speed (he was happy moving because his donkey-friend had just passed by with his group and was not far ahead of us) I fell and lost the rope. The donkey stopped, immediately. He did not step on me, nor did he take his chance to run away towards his friend. He just waited for me to get up.

Also I learned from the donkey master that if you are too strict with your donkey he will snap and completely stop moving, no matter what. The last few days of our trip when in the early morning I went to get the donkey from his meadow, I just had to call him and he happily came over to me. Yet I won’t go as far to say I started to like him. The trip meant a certain load of dukkha for me, through association with the unbeloved I had to push for seven days. I am sure our donkey was fully aware of that, but I have still no idea whatever he was thinking of me.