After Sesshin

Last week I shared 3 1/2 intense days with nice people practising Zazen, Hitsuzendo (Zen-exercise with brush and ink) and Aikiken (Aikido based exercise with a wooden sword) at Benediktushof Holzkirchen. I much enjoy these Sesshin, since they allow us to focus on our practise for some uninterrupted time. And particularly for me as a teacher, dealing with the various characters is always a good exercise …

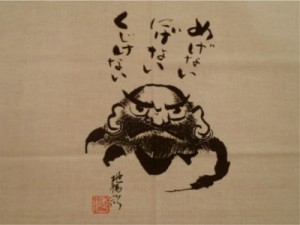

Zazen and Hitsuzendo went surprisingly well without any problems. I much enjoy when I don’t have to talk too much for getting the writing periods running smoothly and there is a good concentrated working atmosphere in the room: not just when it’s my turn writing on a sheet of (news)paper, but also helping and observing the others.

Said that, eight beginners handling wooden swords can be thrilling … so I handed out a sheet of paper the day before with written safety instructions, and repeated the main points how to avoid accidents before we started exercising. Nevertheless, one person got injured, of all participants the most experienced one with the sword (I was already looking forward to having such a skilled swordsman available for demonstration): he twist his ankle when walking down the stairs on the way back from the Dojo. My warning “most accidents happen before or after the actual practise when concentration slows down!” didn’t help … I hope he gets well soon!

Said that, eight beginners handling wooden swords can be thrilling … so I handed out a sheet of paper the day before with written safety instructions, and repeated the main points how to avoid accidents before we started exercising. Nevertheless, one person got injured, of all participants the most experienced one with the sword (I was already looking forward to having such a skilled swordsman available for demonstration): he twist his ankle when walking down the stairs on the way back from the Dojo. My warning “most accidents happen before or after the actual practise when concentration slows down!” didn’t help … I hope he gets well soon!

After Sesshin it is once more lots of packing and un-packing at home, finally washing the brushes one more time. Always when these brushes are hanging above the sink in my kitchen slowly dripping out, I know the Sesshin is really over … and I let my concentration slip for a few minutes over a cup of tee.

–

P.S.: Since I got a related question: no, I am not using the soap you can see in the background of the picture to wash my brushes, only cold water! Never use soap, and warm water only if the ink dried into the hair (which ideally does never occur).