Topys Turvy Zen

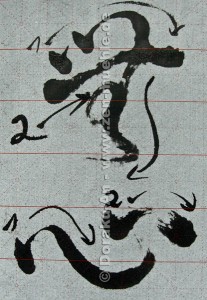

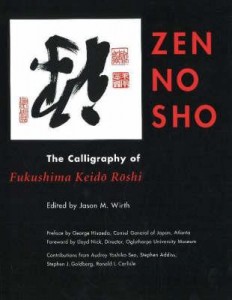

The other day I joined a discussion on the web concerning a book called “Zen no Sho, The Calligraphy of Fukushima Keido Roshi”. The Roshi’s brushwork is very inspiring indeed, but unfortunately the processing of the book came along with certain errors, namely the character 「禅」(Zen) printed upside down on the cover. I vividly remember how upset my former teacher was about “such a carelessly done work in the name of Zen Calligraphy”, alas I never received any response from the editors concerning my letter suggesting some errata.

The other day I joined a discussion on the web concerning a book called “Zen no Sho, The Calligraphy of Fukushima Keido Roshi”. The Roshi’s brushwork is very inspiring indeed, but unfortunately the processing of the book came along with certain errors, namely the character 「禅」(Zen) printed upside down on the cover. I vividly remember how upset my former teacher was about “such a carelessly done work in the name of Zen Calligraphy”, alas I never received any response from the editors concerning my letter suggesting some errata.

Often things in Zen surprise us, as if coming from a world upside down. The message sounds like “say good-bye to your concepts of how things should be, weather something is wrong or right … just let it go!”, and the more scholarly type of Zen adept might explain about the wrong dualism of good and bad versus the correct (sic!) non-dualistic approach of Zen.

Sometimes I am asked by puzzled students, if really from a Zen point of view everything is equal, no good or bad, no wrong or right does exist. War, rape and murder are equally good or bad as compassion and peace-work? Criticizing a famouse Roshi of molesting young female students just reflects a not yet developed state of mind, stuck in a dualistic point of view?

The answer can be found in the 般若心経 (Heart Sutra):

無無明亦無無明尽 (むむみょうやくむむみょうじん)

No ignorance and also no extinction of it

So, even the correct non-dualistic view is dualistic, the concept of “no right or wrong” goes far beyond the idea that there is simply no right or wrong … so what is the consequence for our every day life, if we want to consider that Zen point of view?

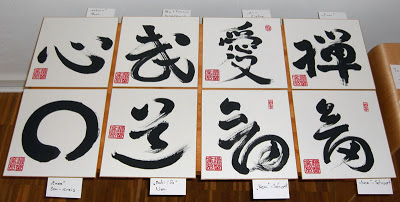

The simple message is to just take full care of what we are doing in this very moment … what I do right here right now, fully concentrated and to the best of my skills, this is beyond right or wrong, it is just it. Working and living like this, moment by moment, is not only very fulfilling, it also makes it very unlikely that a calligraphy 「禅」 on the cover of a book will be printed upside down. Or that I will be upset or disappointed about the outcome of my calligraphy. That trace of ink, that is just me …