Daydreaming

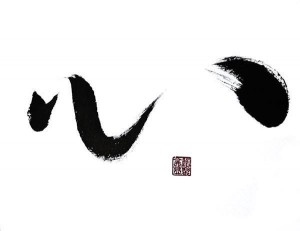

About 15 Years ago, during the lunch-break of a Zen-Seminar at my old Aikido-Dojo in Bavaria, my former teacher brushed for me the character 夢 (YUME/dream) on a large paper. I believe it is one of the best pieces he ever wrote, reflecting so well the atmosphere of that beautiful sunny day. This YUME has been on display ever since, at my home, my office for years and now at my Dojo.

Last week a lady visited the Dojo in search of a calligraphy as a special birthday gift. After inspecting my own brushwork for some time she spotted that YUME and said: “Oh, THIS ONE is beautiful!”. I explained why it is not for sale, and offered to write a “similar one” instead.

When a few days later my phone rang and the lady agreed to my offer, I knew I was in trouble. Writing nice calligraphy is one thing, fulfilling the frivolous promise to produce an equivalent copy of my former teacher’s master-piece is another story.

It is impossible for me to brush a vibrant piece of Zen-calligraphy if I bear any doubt in my heart, any fear, any worries … even the slightest hesitation will leave its trace on the paper, clearly visible to the expert and lay-person alike. Like a happy child loudly singing on the street, an unburdened state of mind freely playing with the technical skills acquired over years of practice is the only way to express myself with brush and ink. It cannot be pushed, if “ME” wants to write a masterpiece, all you can see later in my brush-stroke is either my fear to fail, or MY BIG EGO.

Writing my former teacher’s YUME without even thinking of it, what an exercise!

Did I succeed? The friendly customer seemed delighted with the outcome of my efforts when she came to pick up her YUME the other day. I gave her the best out of seven versions, though I believe the quick warm-up I first brushed on a newspaper was maybe even slightly better …