Petty Things

When my former teacher occasionally was entitled “Zen Master” by visitors, he usually replied, “I am not a Zen Master, not even a janitor” (“Hausmeister” in German, which literally translates “house master”). Sometimes people inviting him to teach a Sesshin wrote “Roshi” on the advertisement poster, which he cheekily translated for us 浪師 into Japanese, taking the first character 浪 from the word “Ronin“, known as the master-less or unemployed samurai roaming feudal period Japan. Roshi, the “travelling teacher”.

I closely studied and worked with him for thirteen years and never ever considered to quit because he was not an “officially certified Roshi” … all the years I was sure he is the best teacher I could find.

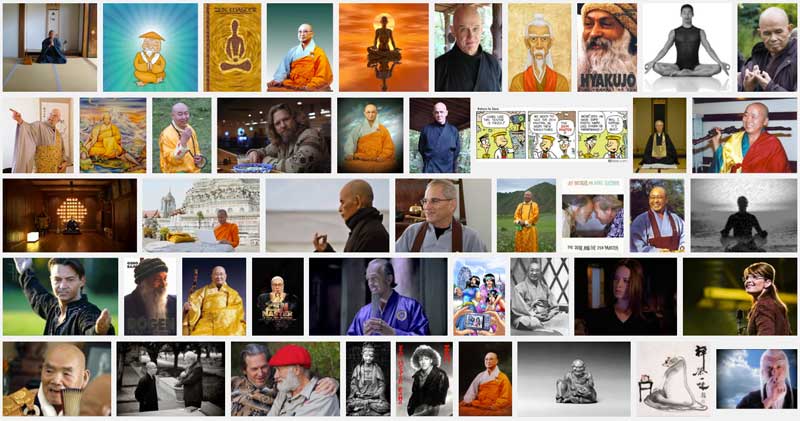

Result of a google-search for “zenmaster”. Amongst other notables, Sarah Palin, Chandra Mohan Rain (“Osho”) and “Zen Master Rama” pop up.

I don’t have much confidence in titles or ranks handed down from one person to another. If there was only one of them in the past going wrong, an ever growing avalanche of “wrong heirs” inevitably follows. Just imagine passing on a driving license would be allowed to everyone holding one …

In an ideal world, all titles and ranks (if required at all in an ideal world) should be issued exclusively through institutions governed by a group of peers, in order to provide a minimum of control. In the real world for example, I cannot “transmit” my PhD (the highest academic rank one can acquire) to anyone, even when I am fully convinced my best and most dedicated student deserves it. It is the faculty alone who can do so, following certain well defined rules. And the whole process is transparent and public.

What then is handed down or transmitted in a Zen-Buddhist context from teacher to student? It is the Dharma, of course. Though, quite opposite to a contemporary reading of so called tradition, I understand the “Dharma transmission” as an ongoing process, beginning the day the novice decides to study with a certain teacher. A process, which continues even after one’s teacher passed away (physically or emotionally in the student’s heart) and which doesn’t end with one’s own death, in case there is a next generation of students one accompanies.

For the individual, Dharma transmission is a life-long exchange with our spiritual ancestors. It never occurs “just once”, and it is never completed … what a nonsense idea is it to certify such thing! What would you say if I’d consider to certify the river behind my Dojo is ever flowing?

I don’t believe the image of a “light transmitted from candle to candle” is very appropriate to illustrate “Dharma transmission”. The transmission is maybe much better understood as a thick long rope, made up of uncountable interwoven short thin strings. The longer the overlap between the individual strings, the stronger the rope is. And never ever an individual string supports the rope as a whole.

It might be assuring for the novice student to learn the teacher’s teacher had enough confidence into his or her insight and abilities to issue some kind of teaching license. Though, what does that really proof? In the worst case nothing more than that my old teacher misjudged me? That he maybe had gone a bit senile in his old days? Or that he hoped to strengthen ties between us, possibly for his own benefit? What does my own teaching license proof, beyond the fact that my teacher, at a certain moment in our life, believed it was a good idea to certify that in his eyes I am qualified to teach?

My former Aikido teacher, Kobayashi Hirokazu, never performed any examination or gave any ranks or titles to his students (1). He used to say “what I give you are the pearls, it is your task to make a necklace out of it!”. That was all we got from him, and it was plenty enough!

If there was not such a hype concerning “Zen Master” or “Roshi” titles in the community – titles, sometimes supporting old abusive men or half-baked part-time Zen-teachers (2) who would have most likely been out of business before long if they did not “hold” (and potentially one day “hand down”, of course…) such titles – I wouldn’t even care to write these few lines. I never trusted or mistrusted a spiritual companion because of being a certified “Master” or “Roshi” or not, it plays absolutely no role. Thinking about it any longer I feel is a waste of time … time, better spent transmitting the Dharma.

—

(1) I witnessed several discussions on the graduation topic and the associated issue of forming an organisation with Kobayashi Sensei. Clearly I do remember he always strictly refused to support such plans. Instead, he provided official Dan certificates issued from Aikikai upon his recommendation to everyone who asked him for such favour (including people he did neither know by name nor face). Said that, also with Kobayshi Sensei there is a story about graduation and mandate to form an organisation issued on his death bed. I don’t know, I was not on his side when he passed away.

(2) This is even more obvious considering how significantly the meaning behind “Dharma transmission” differs between Soto- and Rinzai-Zen:

In Soto-Zen “Dharma transmission” (shiho) is about equivalent to a Bachelor’s degree in academia. It is a prerequisite for acquiring the lowest rank within the Soto-Shu‘s system and does not even qualify one to teach. Nevertheless, in the West Soto-Zen students with “Dharma transmission” occasionally sell themselves as “Zen Master”, boldly ignoring the meaning of shiho in the context of the Japanese system they received it.

In Rinzai-Zen, a “Dharma transmission” (inka shomei) is equivalent to being awarded a Nobel Prize. Only 50 to 80 properly certified Rinzai Zen Masters with inka shomei do exist in Japan, it is a process which requires decades of dedicated studies within the system (notably, to successfully complete working through a huge collection of Koan).