To See or Not to See

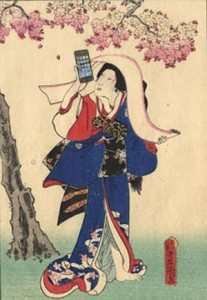

Cherry blossom was at it’s peak when I returned from a five days Zen-practise at Joutoku-ji in the countryside North-West of Kyoto. Once a great party appreciating impermanence under blooming trees, hanami of the digital age appears to become more and more a picture-hunting event. Not a single beautiful tree without masses of people watching it through the displays of their mobile-phones or more expensive photography equipment. There must be a billion pictures of cherry blossoms taken by the Japanese and tourists every year! Unable to simply enjoy the fleeting beauty, I couldn’t withstand the temptation of adding not just a few digital blossoms to the virtual cherry orchard.

Cherry blossom was at it’s peak when I returned from a five days Zen-practise at Joutoku-ji in the countryside North-West of Kyoto. Once a great party appreciating impermanence under blooming trees, hanami of the digital age appears to become more and more a picture-hunting event. Not a single beautiful tree without masses of people watching it through the displays of their mobile-phones or more expensive photography equipment. There must be a billion pictures of cherry blossoms taken by the Japanese and tourists every year! Unable to simply enjoy the fleeting beauty, I couldn’t withstand the temptation of adding not just a few digital blossoms to the virtual cherry orchard.

Obai-in, a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji in the North of Kyoto had a special opening these days. The temple is famous for it’s beautifully maintained garden, one of the finest in Kyoto (designed by Sen no Rikyu), yet photography is strictly forbidden. What a relief, to enjoy the beautiful place for more than an hour until it closed, without even thinking about taking a single picture! This experience made me once more realise how much my camera sometimes obstructs what I actually could see and experience, if it was not just through a viewfinder or display.

In this week’s “ZEITmagazin” I read an interview with Elton John. I don’t know much of his music, but part of the interview addressed a similar point:

What’s all that nonsense with mobile-phone pictures? What kind of people is that who come with iPads to the concerts and shoot everything? They don’t watch the show at all, but only stare at their iPad! That’s sick! Elton John (1)

For me it remains a tightrope walk to find the balance between photography as a Zen-way and true Zen-practise, or experience taking pictures as just getting in the way of any real experience.

–

(1) Interview with Elton John, “Das beste Bett aller Zeiten”, ZEITmagazin Nº 16/2014 (the English quotation is my back-translation from the German text).